Book: Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan. (481 pages)

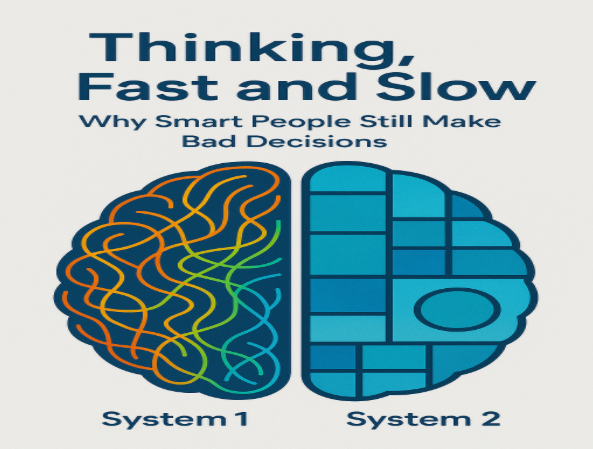

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman is a seminal book that explores the dual systems of thinking that drive human decision-making. Kahneman, a psychologist and Nobel laureate, introduces two systems of thinking that shape how we interpret and respond to the world around us. He is the first non-economist to win a Nobel Prize in Economics and is also credited with creating a new branch of study in economics—Behavioral Economics. Kahneman argues that understanding how our two thinking systems work can help us make better decisions. He advises that we should be aware of biases and try to use more thoughtful, slow thinking (System 2) when important decisions are at stake.

In 1944, two economists, Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, derived their expected utility theory from a few axioms. Neumann and Morgenstern stated that if your choices are logically consistent, then you behave as if you maximize expected utility. This theory has a mathematical foundation based on rationality under risk. Expected utility theory dominated economic thinking for much of the 20th century and remained the standard model of rational decision-making well into the 21st century, even as behavioral research revealed important limitations. Kahneman and Amos Tversky made a breakthrough in 2011 by systematically describing how humans make risky choices without assuming anything about their rationality (pp. 270-271). They received a Nobel Prize for their groundbreaking work. Kahneman’s central thesis is that while humans are capable of both fast, intuitive decisions and slow, reasoned decisions, they often rely too heavily on the former, leading to errors in judgment and suboptimal decisions. They concluded that humans can make more informed decisions and reduce suboptimal outcomes if we are aware of these biases and thinking processes.

Kahneman stated that “intelligence is not only the ability to reason: it is also the ability to find relevant material in memory and to deploy attention when needed” (p.46). He noted that the brain has two systems—System 1 and System 2. Memory is a trait of System 1, but with more time and thought, System 2 can be used for accurate reasoning. He emphasized that there is a reward in being calm, deliberate, and kind. The familiar advice “act calm and kind no matter how you feel” (p.54) is indeed wise; in time, you will likely be rewarded by truly feeling calm and kind. In his book, Kahneman asks three fundamental questions:

- Why do we sometimes make quick decisions that we later regret?

- Why do our best-laid plans often fall short?

- Why do experienced professionals still fall into the same mental traps—over and over again?

Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow offers a compelling explanation. As a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist, Kahneman presents a framework for understanding how we think, how we make decisions, and—more importantly—how we misjudge situations without even realizing it. In this article, I’ve broken down the core concepts of the book and tried to show how they apply to professional life—from leadership to planning and risk assessment.

The Two Systems That Run the Mind

Kahneman’s big idea is that our brain operates using two systems:

System 1: Fast, Intuitive Thinking

-

- It’s fast and efficient

- But it’s also prone to biases and errors

We rely on System 1 constantly, especially when we’re under time pressure or multitasking. The problem is, we often trust it too much.

System 2: Slow, Deliberate Thinking

This system is slower and more logical. It takes effort and concentration. We engage System 2 when solving a complex problem or making an important decision.

- It’s more accurate

- But it’s also mentally taxing, so we avoid using it unless absolutely necessary

Where Smart People Go Wrong: Common Mental Biases

1. Anchoring Bias

We give too much weight to the first piece of information we hear.

Example: If a consultant says a project will cost $500K, that number becomes the mental anchor—even if the actual cost turns out to be very different.

2. Availability Heuristic

We judge likelihood based on what’s easiest to recall.

Example: After hearing about a cybersecurity breach in the news, leaders might over-prioritize digital security—even if the real risk lies elsewhere.

3. Loss Aversion

Losses hurt more than equivalent gains feel good. This makes us risk-averse, even when a calculated risk is the smarter move.

Example: A team may pass on a new market opportunity because the potential downside “feels” more significant than it is.

4. The Planning Fallacy

We consistently underestimate how long tasks will take and how many resources they’ll require.

Sound familiar? Most project timelines.

Why Intuition Can Be Misleading

Kahneman doesn’t say we should ignore our intuition—but he emphasizes that intuition without experience is dangerous. In high-stakes or unfamiliar situations, System 2 should be leading the way. For experts with deep domain knowledge, intuitive decisions can be highly reliable. But for most people, most of the time, gut feelings are shaped by emotion, bias, and incomplete data.

Prospect Theory: Rethinking Risk and Reward

Traditional economics assumes people act rationally and weigh risks logically. Kahneman and his collaborator, Amos Tversky, found that we do not behave like that.

According to Prospect Theory, people:

- Overvalue potential losses

- Undervalue potential gains

- Make inconsistent decisions under uncertainty

Example: If faced with choice of a guaranteed $100 payout or a gamble that has a 50/50 chance to win $200, most people choose the $100 payout, even though the gamble has the same expected value. These tendencies can lead to suboptimal decisions—whether you’re investing, hiring, or launching a new product.

Implications for Leadership and Decision-Making

Understanding how we think isn’t just academic—it’s practical.

- Leaders can design better processes by reducing reliance on gut instinct alone.

- Teams can improve project planning by factoring in bias and uncertainty.

- Organizations can make more resilient, rational strategies by recognizing the limits of intuition.

Kahneman’s work reminds us that slowing down to think clearly has a competitive advantage—especially in a world that constantly demands speed.

Final Thought

Kahneman’s quote sums it up best: “Intelligence is not only the ability to reason; it is also the ability to find relevant material in memory and to deploy attention when needed.” We all like to think we’re rational decision-makers. But Thinking, Fast and Slow shows that even the smartest minds fall into predictable traps. The key is being aware of them—and knowing when to slow down.

Over to You:

Have you seen these biases play out in your work or leadership style? How do you create space for better, slower thinking in your team or organization? Leave your comment.