Negussie Tilahun, Ph.D., MS, MSc., MA

Affiliation:

International Health Information Management Consultancy Group

Email:

Negussie.tilahun@ihitmconsultancy.org

Date:

November 2025

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the current state of cloud computing in Ethiopia. The analysis focuses on three factors that determine its implementation: (1) organizational factors (top leadership’s management strategy and hospital readiness), (2) environmental or external factors (regulations and standards), and (3) technological factors (complexity, relative advantage, and compatibility). The study is based on a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference publications, online databases, and case studies conducted in Debre Berhan City—about 57 miles northeast of Addis Ababa—during September/October 2019, and at Finote Selam Hospital in Bahir Dar, about 210 km north of Addis Ababa, in January 2022.

The findings indicate that a dynamic management strategy is essential for the successful implementation of cloud computing in healthcare. Cloud computing is increasingly recognized for modernizing healthcare systems by lowering data-storage costs and improving service availability. A successful transition requires an adaptive and value-driven approach that benefits both healthcare providers and patients. This approach—termed digital transformative leadership—is dynamic, participatory, and guided by management and quality metrics that measure organizational progress and performance.

Keywords: cloud computing, Ethiopia, healthcare management, digital transformative leadership, health information systems

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to understand the current state of cloud computing in Ethiopia. The analysis focuses on three factors that determine the implementation of cloud computing: organizational, environmental, and technological. Organizational factors include top leadership and management approach; environmental factors include regulations and standards; and technological factors include complexity, relative advantage, and compatibility. The study is based on a systematic literature review of high-quality, peer-reviewed journal articles, conference publications, online databases, and case studies conducted in Debre Berhan City (September/October 2019) and Finote Selam Hospital in Bahir Dar (January 2022).

Background

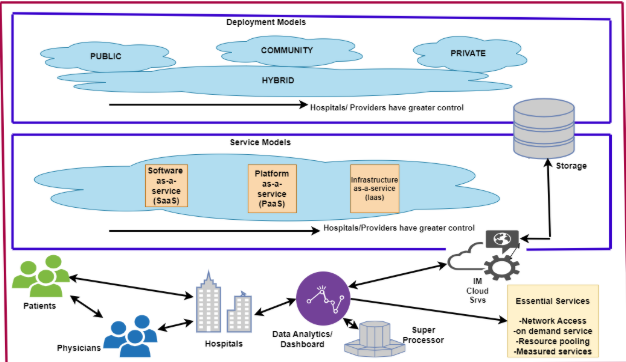

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) define cloud computing as “a paradigm for enabling network access to a scalable and elastic pool of shareable physical or virtual resources with self-service provisioning and administration on demand” (Miyachi, 2018, p. 8). Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of cloud computing in healthcare. Cloud computing addresses two major challenges in healthcare delivery: enhancing healthcare performance and reducing the cost of data storage by making services available on demand. It enables hospitals to provide healthcare services at a lower cost by streamlining administrative processes, reducing paperwork, and automating routine tasks (Ciarli et al., 2021). Cost reduction occurs in two ways. First, hospitals do not need to develop extensive data infrastructure for storage, maintenance, and processing. Second, payments are typically made only for the services used, often on a pay-as-you-go basis (Mujinga & Chipangura, 2011). Consequently, cloud computing provides clinical data or information required by a doctor at a lower cost.

Cloud computing can be deployed through public, community, private, or hybrid models. The private model offers greater control for hospitals or healthcare organizations. Deployment models include Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), with IaaS providing hospitals and healthcare providers greater control over hardware and software. Cloud computing in healthcare provides essential services such as network access, on-demand availability, and resource pooling. The adoption of cloud computing technologies has significantly increased in developing countries following the COVID-19 pandemic (Alashhab et al., 2021). However, many hospitals in Africa still lack the organizational and management structures required to support effective implementation of cloud computing (Matchaba, 2019).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of cloud computing in healthcare

As Figure 1 illustrates, cloud computing can be used as an ICT (Information and Communication Technology) tool to enable both patient-to-doctor and doctor-to-doctor communication. The enhanced decision-making capabilities help improve the efficiency of healthcare systems (Zeadally & Bello, 2021). Patients also benefit from doctors’ comprehensive approaches to treatment. Cloud computing enables the development of an effective Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) that allows clinicians to perform a wide range of activities, such as monitoring vaccination coverage, understanding disparities in health coverage, following treatment protocols, and so forth. In general, a CDSS can be used to assess the effectiveness of healthcare delivery by considering the impact of various health policies and practices.

A Systems Approach to Explaining the Current Ethiopian Healthcare Delivery System

This analysis applies organizational systems theory to understand the Ethiopian healthcare delivery system. Organizational systems theory considers the entire system and the relationships among its parts, rather than focusing on isolated components (Kast & Rosenzweig, 1972). The theory emphasizes the need to understand both the individual components of a system and their interrelationships in order to evaluate the potential for introducing technological innovations and their likely outcomes. Furthermore, the theory helps to evaluate policy options, understand processes, identify inefficiencies, improve quality of care, and enhance policymaking capabilities (Flood & Carson, 2013; Clarkson et al., 2018).

The Ministry of Health (MoH) implemented a broad range of reforms in 2015 in an effort to meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (FMOH, 2015). The MoH established the Health Management Information System (HMIS) unit, which is responsible for health data recording, management, and dissemination. It also decentralized the management of the public health system to regional health bureaus and implemented the mobile-based national digital electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS), designed to capture data from the health extension program and other community-level services (EMH, n.d.).

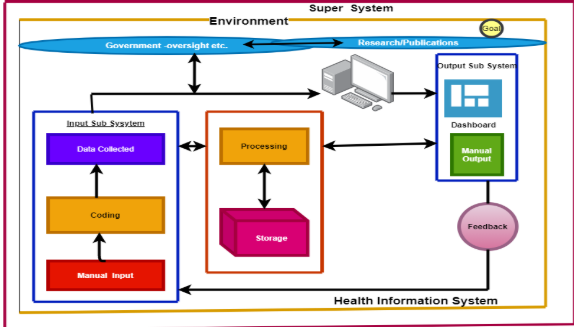

Health data are also collected by the Central Statistics Agency (CSA) and the Ethiopian Nutrition and Health Research Institute (NHRI)—a specialized autonomous agency under the Ministry of Health responsible for collecting data on public health emergencies. However, the absence of an e-health policy and the lack of coordination among various government agencies have created major challenges. Additionally, there are no standardized guidelines or procedures to ensure the quality of collected data, and the country still lacks a national health IT policy. The absence of national policies and standards governing the development and implementation of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) could result in systems from different vendors being non-interoperable. Figure 2 presents a schematic representation of the Ethiopian healthcare system.

Figure 2. Illustration of Ethiopia’s dual health informatics system

The Ethiopian healthcare system combines manual and electronic data collection systems. This hybrid arrangement leverages both paper-based and electronic tools to streamline workflows, enhance communication, and improve patient care (Alzamanan et al., 2022).

1. Goal

The goal of the Ethiopian healthcare system is “to promote the health and well-being of society through providing and regulating a comprehensive package of health services of the highest possible quality in an equitable manner” (MoH, n.d.). The major components of the Ethiopian healthcare delivery system are as follows:

2. Manual Inputs

As explained in the previous section, the healthcare delivery system is hierarchical. The lowest level or subunit is a woreda hospital or clinic, which collects a wide range of data and generates daily, monthly, and annual reports. These units produce aggregate longitudinal data in five broad categories:

- Family planning, antenatal care, delivery, safe abortion, and PMTCT;

- EPI, vaccine wastage rate, child health, and illness management;

- LBW, GMP, SAM screening, VAS, deworming, and IFA;

- ART by regimen, newly started, and retention;

- Malaria, VIA, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

Hospitals also collect socio-demographic data. However, “the implementation and diffusion of eHealth technology in Ethiopia is still in its infancy” (EMH, 2019, p. 10). In recent years, the country introduced DHIS-2 Tracker, an extension of the DHIS-2 platform. “The Tracker shares the same design concept as the overall DHIS-2. The DHIS-2 Tracker is a powerful HMIS tool for following up on health programs and sharing critical clinical health data across multiple health facilities” (Hlaing & Zin, 2020, p. 15). DHIS-2 Tracker enables several types of EMR analysis.

3. Coding/Processing

The processing subsystem transforms manually inputted data into digital records by transcribing them into Excel or DHIS-2. The complexity of this step varies depending on factors such as the shortage of trained personnel and the lack of standardization, which make the transition from paper to electronic databases challenging.

4. Output Subsystems

5. Feedback

6.Government Oversight

At the highest hierarchical level, the MoH designs policies and provides oversight. In 2015, the Ministry developed the Health Sector Transformation Plan, which established the Information Revolution (IR) to create evidence-based decision-making capabilities by improving clinical data collection, analysis, and dissemination (PATH, 2019). The plan also emphasizes cultural and attitudinal changes regarding data management and the perceived value of information (FMOH, 2016). In the same year, the Ethiopian Data Use Partnership (DUP) was created to establish a standardized HMIS, eHealth architecture, HIS governance, and improved data utilization. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) provided funding to improve HIS performance, sustainability, and strengthen information culture in line with the IR.

At Bahir Dar Finote Selam Hospital, electronic health records (EHRs) are used for storing patient information, scheduling appointments, and accessing clinical data, while manual methods remain in use for registration, referrals, and other tasks better suited to paper-based processes. Finote Selam Hospital’s EMR system, Abay CHR (Connected Health Record), is a stand-alone electronic data collection system that does not interface with other systems. Data collection at both Bahir Dar Finote Selam and Debre Berhan hospitals is dual—manual and electronic. Patient encounters begin at the Triage Unit, where the urgency and treatment order are determined. Non-urgent cases are referred to the Recording Unit for registration and treatment. The recording unit collects socio-demographic details, treatment information, and assigns each patient a unique 16-digit identifier consisting of:

- three digits for location,

- three for the institution,

- three for ownership (private or government), and

- four for the individual patient.

This identifier is unique to each hospital and has no relevance outside it. Clinical data collected by nurses and doctors include service start/end dates, diagnoses (using ICD-10 codes), discharge type, and insurance status. These data are entered into Excel and later transferred to DHIS. DHIS, a “health information management system developed through a global collaboration led by the University of Oslo and offered free of charge as a global public good” (Hlaing & Zin, 2019), supports electronic medical records accessible to all medical staff.

Every department—maternity, surgery, etc.—conducts morning review sessions using the EMR dashboard to assess the previous day’s activities and set priorities for the current day. Further analysis is needed to ensure data integrity and process optimization.

Organizational Structure

Each hospital studied is managed by a Board of Directors responsible for strategic decisions and oversight. The Medical Director, appointed by the board, oversees the medical staff and ensures quality healthcare delivery. Department heads manage specific divisions such as maternity and internal medicine, supervise staff, and maintain quality of care. Administrative and support staff report directly to the board, while the IT Department manages EMRs, admissions, and billing systems.

Current State of Cloud Computing in Ethiopia

Ethiopia has implemented several eHealth technologies such as SmartCare, mobile ENAT Messenger, Maternal Interactive Voice Response (IVR), and the Health Management Information System (HMIS) (Ahmed et al., 2020). However, in the past six years, progress has slowed as infrastructure deteriorated due to lack of government investment and widespread social conflict.

The WHO’s 2020 vision emphasizes accelerating the development and adoption of accessible, affordable, scalable, and sustainable digital health solutions. Ethiopia’s healthcare infrastructure remains far below WHO’s recommended standards for doctors, nurses, medical technicians, and facilities (WHO, 2016). Civil conflict in regions such as Amhara, Tigray, and Western Oromia has destroyed existing infrastructure. Internet disconnection, a major consequence of the conflict, poses a significant obstacle to cloud computing, which relies entirely on reliable internet connectivity.

Managing Cloud Health Technology in Ethiopia: A Paradigm Shift

Manyazewal et al. (2021) identified disconnection among stakeholders, lack of supportive environments (electricity, internet), and limited managerial commitment as major barriers to adopting health informatics technologies in Africa, particularly Ethiopia. Health administrators’ and managers’ commitment to change is a determining factor for adopting cloud computing. Health organizations must adopt a technology-focused management approach that considers future demand and scalability (GeeksforGeeks, 2021).

Developing dynamic decision-making capabilities—enabled by real-time data access—can enhance efficiency and reduce costs. Studies identify senior management support and organizational structure as essential determinants for cloud adoption (Aceto & Pescape, 2020; Amron et al., 2019). However, the hierarchical structure of Ethiopia’s healthcare sector is less conducive to the flexible management approach required for technological adaptation (McGrath & McManus, 2021). Senior management determines the development model (public, private, or hybrid cloud) and the delivery model (IaaS, PaaS, or SaaS). Implementing these decisions requires reorganizing the hierarchical management structure to create interdisciplinary, agile, and adaptive teams.

Implementation Metrics for Cloud Computing

1. Operational Efficiency – Reduce medical and administrative errors through automation; streamline patient information management; improve communication and patient satisfaction.

2. Financial Performance – Increase revenue and reduce costs.

3. Employee Engagement – Measure turnover, productivity, and commitment.

4. Quality and Performance – Track error rates and patient satisfaction.

5. Innovation and Adaptability – Monitor R&D investment, new product launches, and market responsiveness.

6. Employee Development – Track training hours, promotions, and talent retention. Continuous learning is essential for managing cloud technologies (Canlas, 2022).

7. Ethics and Equity – Reduce disparities in healthcare access (Khayer et al., 2020).

Quality Measurement Metrics

Quality management plans strengthen organizational performance and readiness for digital transformation (Nguyen et al., 2018). Leadership should adopt SMART performance goals—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound—when transitioning to cloud computing. Key indicators include:

- First-time resolution rate.

- Error or defect rate.

- Response time to patient issues.

- Compliance rate with healthcare regulations (e.g., HIPAA).

Steps Toward Digital Management Goals

- Identify the type of cloud computing that meets the organization’s cost-benefit needs.

- Restructure management to enhance agility and collaboration.

- Expand access to healthcare and reduce disparities through regular monitoring and evaluation.

- Promote lifelong learning and leadership engagement in technology adoption.

Conclusion

This study examines the current state of cloud computing in Ethiopia’s healthcare system and highlights the decisive role of digital transformative leadership in shaping its adoption. Using a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles, national policy documents, online databases, and fieldwork conducted in Debre Berhan and Finote Selam hospitals, the analysis evaluates three broad determinants—organizational, environmental, and technological. Together, these factors reveal both the promise and the deep structural constraints affecting Ethiopia’s transition toward modern digital health systems.

Cloud computing is increasingly recognized as an essential infrastructure for improving healthcare quality, reducing the cost of data storage, and enabling timely clinical decision-making. By eliminating the need for costly in-house servers and allowing pay-as-you-go service models, cloud technologies can help hospitals shift resources from administrative overhead to direct patient care. In clinical settings, cloud-based systems support real-time access to medical records, strengthen decision-support tools, and improve patient-to-doctor and provider-to-provider communication. These capabilities are particularly important for countries such as Ethiopia, where resource constraints, paper-based processes, and fragmented data systems remain prevalent.

The study uses a systems-thinking approach to show that Ethiopia’s healthcare environment is characterized by parallel manual and electronic subsystems that do not fully interoperate. Hospitals generate substantial volumes of data—ranging from MNCH and EPI to TB/HIV, NCDs, and emergency care—but the absence of national e-health standards, insufficient technical guidelines, and a lack of organizational readiness hinder the transition from paper to digital platforms. Although DHIS-2 and DHIS-2 Tracker offer powerful tools for harmonizing health information, their use is constrained by inconsistent training, poor connectivity, and fragmented institutional arrangements. The result is a dual system where manual registers and Excel-based processes coexist with emerging digital tools, limiting the scalability and reliability of electronic health records.

Field observations from Debre Berhan and Finote Selam confirm these structural gaps. Both hospitals operate hybrid workflows in which triage, registration, and several clinical processes are still paper based, while electronic systems such as Abay CHR store basic patient information but lack integration with other platforms. Data management remains heavily dependent on manual transcription, and the absence of a unique national patient identifier restricts continuity of care. Despite these limitations, routine use of EMR dashboards during morning clinical reviews shows that clinicians value digital tools when they are available, functional, and supported by the organizational culture.

A major finding of the study is that cloud computing cannot succeed through technology alone. Leadership—rather than infrastructure—is the determining factor. Digital transformative leadership is characterized by adaptability, cross-departmental collaboration, and commitment to evidence-based management. Leaders guide the selection of cloud deployment models (public, private, community, or hybrid) and choose between SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS delivery options. More importantly, they foster the organizational culture required to support these decisions: skilled personnel, continuous learning, interoperable systems, and reliable feedback loops.

The study identifies several metrics that organizations should use when transitioning to cloud-based health management systems. These include operational efficiency (error reduction, smoother workflows), financial performance, employee engagement, patient satisfaction, innovation capacity, and equity in service delivery. Quality improvement must be anchored in SMART indicators that are measurable and tied to clinical and administrative outcomes. Ethiopia faces major barriers, including civil conflict, poor infrastructure, and lack of legal frameworks for data protection. However, gradual implementation—starting with pilot hospitals—offers a feasible path forward. As Montealegre (1999) found in Latin America, incremental transformation increases success rates.

Overall, the study concludes that cloud computing offers a powerful opportunity to modernize Ethiopia’s healthcare delivery system. However, its successful implementation requires more than technology. It demands leadership that is dynamic and future-oriented, management structures that are agile and participatory, and national policies that ensure interoperability and data quality. A coordinated, value-driven approach—supported by robust governance, reliable connectivity, and continuous learning—can enable Ethiopia to build a resilient digital health ecosystem that benefits both providers and patients.

Appendix 1

Table 1: Hospital Output Reports Produced by Public General Hospitals in Ethiopia (Amhara Region) | ||||

(Case study at Bahir Dar Finote Selam & Debre Birhan Hospitals) | ||||

Report Name | Frequency | Main Contents / Indicators | Primary Users | Purpose / How It Is Used |

1.OPD Service Report (HMIS 105A) | Monthly | OPD visits by age/sex, new/repeat, top 10 causes of morbidity, emergency visits, referrals | HMIS officer, clinical departments, RHB/ZHB | Monitor disease trends, adjust staffing, update clinical guidelines |

2.IPD Morbidity & Mortality Report (HMIS 105B) | Monthly | Admissions, discharges, deaths, ALOS, BOR, major causes of IPD morbidity/mortality | Hospital management, clinical teams, RHB | Improve inpatient care, analyze case fatality rates, allocate beds |

3.Maternal & Child Health Report (MNCH) | Monthly | ANC (1 & 4+), skilled deliveries (SVD, assisted, C-section), PNC, FP, neonatal deaths, stillbirths | Maternity unit, HMIS, maternal health focal person | Monitor maternal/neonatal outcomes, guide MPDSR actions |

4.EPI / Immunization Report | Monthly | Vaccine coverage (BCG, Penta, PCV, Measles), dropout rates, outreach vs static | EPI focal, RHB/ZHB | Ensure vaccine coverage, identify dropout causes |

5.HIV/ART & PMTCT Report | Monthly/Quarterly | Number tested, ART initiations, total on ART, retention, LTFU, viral load suppression | ART clinic, PHCU HIV team, RHB | Improve retention, ART supply forecasting, program performance |

6.TB & Leprosy Report | Monthly/Quarterly | New/retreatment cases, TB category, GeneXpert tests, treatment outcomes, contact tracing | TB clinic, NTLP, RHB | Surveillance, drug forecasting, treatment success monitoring |

7.Malaria Report | Weekly/Monthly | Suspected/tested cases, positives by species, severe malaria, deaths | HMIS, malaria focal, RHB | Outbreak detection, ensure RDT/ACT availability |

8.Nutrition (TFU/SC) Report | Monthly | SAM admissions, cures, defaulters, deaths, SC caseload | Pediatrics/SC, RHB nutrition team | Monitor trends, procure RUTF, improve case management |

9.NCD Chronic Follow-Up Report | Monthly/Quarterly | HTN, diabetes follow-up numbers, defaulting | Hospitals with NCD clinics | Manage chronic disease services |

10.MPDSR Report | As cases occur; monthly summary | Case reviews, causes of death, contributing factors, action plans | Maternity, MPDSR committee, RHB | Reduce avoidable maternal/neonatal deaths |

11.M&M Audit Report | Monthly | Ward-level death reviews, complications, case-fatality rates | Clinical directors, RHB | Improve quality of care, clinical decision-making |

12.Clinical Audit Reports | Monthly/Quarterly | C-section audit, sepsis audit, antibiotics use, ART default tracing | QI committee, departments | Improve adherence to clinical standards |

13.IPC & Patient Safety Report | Monthly | SSI rates, hand hygiene compliance, needle-stick injuries, waste management | IPC focal, QI committee | Reduce infections and improve patient safety |

14.Pharmacy/APTS Monthly Report | Monthly | Stock status, tracer drug stock-outs, consumption, expiry, revenue, prescription audits | Pharmacy head, EPSA, RHB | Drug forecasting, revenue tracking, APTS compliance |

15.Laboratory Monthly Report | Monthly | Test volumes, rejection rates, TAT, EQA results, reagent stock | Lab head, EQA providers, RHB | Maintain lab quality, ensure reagent supply |

16.RRF (Report & Requisition Form) | Every 2 months | Pharmaceutical and supply requisition to EPSA | Pharmacy, EPSA | Ensure continuous drug/supply delivery |

17.Finance & Revenue Reports | Monthly/Quarterly | Revenue, expenditures, budget utilization, exemptions/waivers | Finance unit, hospital management | Budgeting, resource allocation |

18.Human Resource Report | Monthly | Staff count, vacancies, turnover, trainings | HR office, RHB | Workforce planning |

19.Equipment & Infrastructure Report | Monthly/Quarterly | Functionality of key equipment, maintenance, utility interruptions | Engineering unit, hospital management | Maintenance planning, capital investment |

References

Aceto, G., Persico, V., & Pescapé, A. (2020). Industry 4.0 and health: Internet

of things, big data, and cloud computing for healthcare 4.0. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 18

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2452414X19300135

telemedicine development in Sub-Saharan African Countries. In 2016 IEEE EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES) (pp. 551-556). IEEE.

Ahmed, M. H., Bogale, A. D., Tilahun, B., Kalayou, M. H., Klein, J., Mengiste, S. A., &

Endehabtu, B. F. (2020). Intention to use electronic medical record and its predictors among health care providers at referral hospitals, north-West Ethiopia, 2019: using unified theory of acceptance and use technology 2 (UTAUT2) model. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making,20(1), 1-11.

Alashhab, Z. R., Anbar, M., Singh, M. M., Leau, Y. B., Al-Sai, Z. A., &

Alhayja’a, S. A. (2021). Impact of coronavirus pandemic crisis on technologies and cloud computing applications. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology,19(1).

Alzamanan, A. A., Al Sulaiman, A. S., Albahri, H. M., & Alduways, A. (2022). Improving the

Amron, M. T., Ibrahim, R., Bakar, N. A. A., & Chuprat, S. (2019). Determining factors

influencing the acceptance of cloud computing implementation. Procedia Computer Science, 161, 1055-1063.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877050919319271

Arage, M. W., Kumsa, H., Asfaw, M. S., Kassaw, A. T., Dagnew, E. M.,

Tunta, A., … & Tenaw, L. A. (2023). Exploring the health consequences of armed conflict: the perspective of Northeast Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC public health,23(1).

Atzori, L., Iera, A., Giacomo, M. (2010). The Internet of Things: A survey. Computer

Networks, 54(15), 2787–2805.

Brall, C., Schröder-Bäck, P., & Maeckelberghe, E. (2019). Ethical aspects of digital

health from a justice point of view. European Journal of Public Health,29(Supplement_3), 18-22.

Calzon, B. (2022, June 6). 12 Cloud computing risks & challenges businesses are facing

in these days. Business Intelligence.

https://www.datapine.com/blog/cloud-computing-risks-and-challenges/

Canlas, C. L. M. (2022). The effectiveness of project management credentials and

integrated project management implementation on IT project management success [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Cumberlands].

Chery, K. (2020). Leadership styles and frameworks you should know. Verywell mind.

Ciarli, T., Kenney, M., Massini, S., & Piscitello, L. (2021). Digital technologies,

innovation, and skills: Emerging trajectories and challenges. Research Policy, 50(7), 104289.

Clarkson, J., Dean, J., Ward, J., Komashie, A., & Bashford, T. (2018). A systems

approach to healthcare: from thinking to practice. Future healthcare journal, 5(3), 151.

Cresswell, K., Hernández, A. D., Williams, R., & Sheikh, A. (2022). Key challenges and

opportunities for cloud technology in health care: Semistructured interview study. JMIR Human Factors, 9(1), Article e31246. https://doi.org/10.2196/31246

PATH. (2019). Coordinating digital transformation: Ethiopia

DHIS2. (2019). University of Oslo health information system program.

Dixon, B. E., Embi, P. J., & Haggstrom, D. A. (2018). Information technologies that

facilitate care coordination: provider and patient perspectives. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8(3), 522- 525.

Flood, R. L., & Carson, E. R. (2013). Dealing with complexity: an introduction to the

theory and application of systems science. Springer Science & Business Media.

Furr, N., & Shipilov, A. (2019). Digital doesn’t have to be disruptive: The best results can

come from adaptation rather than reinvention. Harvard Business Review, 97(4), 94–103.

Gana Web. (2023). Five killed in Ethiopia after drone strike hits ambulances (ghanaweb.com).

GeeksforGeeks. (n.d.). Cloud management in cloud computing.

Giordano, C., Brennan, M., Mohamed, B., Rashidi, P., Modave, F., & Tighe, P.

(2021). Accessing artificial intelligence for clinical decision-making. Frontiers in digital health, 3.

Graffeo, A. (2018). Leading science and technology-based organizations: Mastering the

fundamentals of personal, managerial, and executive leadership. CRC Press.

Hlaing, T., & Zin, T. (2020). Organizational factors in determining data quality produced

from health management information systems in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Informatics, 9(4), 10-5121.

Icrc. (2023). Ethiopia: Healthcare crisis in Oromia exacerbated by massive

displacemet. International committee of the Red Cross (iccr,org).

https://www.icrc.org/en/document/ethiopia-healthcare-crisis-oromia-exacerbated-massive-displacement

Jain, D. (2023). Regulation of digital healthcare in India: Ethical and legal

challenges. Healthcare, 11(6), 911.

Kaur, H., Alm, M. A., Jameel, R., Maurya, A. K., & Chang, V. (2018). A proposed

solution and future direction to Blockchain-based heterogeneous medical data in a cloud environment. Journal of Medical Systems,42(156).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10916-018-1007-5

Khayer, A., Bao, Y., & Nguyen, B. (2020). Understanding cloud computing success and

its impact on firm performance: an integrated approach. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(5), 963–985.

Kohnke, O. (2017). It’s not just about technology: The people side of

Liu, P., Astudillo, K., Velez, D., Kelley, L., Cobbs-Lomax, D., & Spatz, E. S. (2020). Use

Lyles, C. R., Nguyen, O. K., Khoong, E. C., Aguilera, A., & Sarkar, U. (2023). Multilevel

determinants of digital health equity: a literature synthesis to advance the field. Annual Review of Public Health, 44, 383-405.

Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Blumberg, H. M., Fekadu, A., & Marconi,

V.C.(2021). The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ digital medicine, 4(1), 1-13.

Matchaba, P. (2019, August). How to start a digital healthcare revolution in Africa in 6

steps.

World Economic Forum.

McGrath, R., & McManus, R. (2021, May-June). Discovery-driven digital. Harvard

Business Review.

MOH. (n.d.). Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Mission, vision and objectives. (moh.gov.et).

https://www.moh.gov.et/mission-vission-objectives

MOH. (2019). Ethiopia Ministry of Health. www.moh.gov.et/

MOH. (2016). Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. Information Revolution Roadmap.

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Miyachi, C. (2018). What is “Cloud”? It is time to update the NIST definition?. IEEE

Cloud computing, 5(03), 6-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20190306204414id_/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/

cbb4/4eca5afb5901b1a95fd8522528f9e0da7851.pdf

Montealegre, R. (1999). A temporal model of institutional interventions for

information technology adoption in less-developed countries. Journal of Management Information Systems, 16(1), 207-232.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07421222.1999.11518240

Mujinga, M., & Chipangura, B. (2011, December 5-7). Cloud computing concerns in

developing economies. 9th Australian Information Security Management Conference, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia.

Nguyen, M. H., Phan, A. C., & Matsui, Y. (2018). Contribution of quality management

practices to sustainability performance of Vietnamese firms. Sustainability,10(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020375

Ogiela, L., Ogiela, M. R., & Ko, H. (2020). Intelligent data management and security in

cloud computing. Sensors, 20(12).

Rahi, S., Khan, M. M., & Alghizzawi, M. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of

telemedicine health services during COVID-19 pandemic crisis: An integrative research model. Enterprise Information Systems, 15(6), 769–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/17517575.2020.1850872

Shahid, J., Ahmad, R., Kiani, A. K., Ahmad, T., Saeed, S., & Almuhaideb, A. M.

(2022). Data protection and privacy of the internet of healthcare things (IoHTs). Applied Sciences, 12(4).

Sheth, A., Jaimini, U., & Yip, H. Y. (2018). How will the Internet of Things enable

Silva, C. R. D. V., Lopes, R. H., de Goes Bay Jr, O., Martiniano, C. S.,

Fuentealba-Torres, M., Arcêncio, R. A., … & da Costa Uchoa, S. A. (2022). Digital health opportunities to improve primary health care in the context of COVID-19: scoping review. JMIR human factors, 9(2).

Vaz, N. (2021). Digital business transformation: How established companies sustain

competitive advantage from now to next. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 978-1119- 75867-9.

Wall, L. L. (2022). The siege of Ayder Hospital: a cri de coeur from Tigray,

Ethiopia. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 28(5).

World Health organization. (2016). Health workforce requirements for universal health

coverage and sustainable development goals. Human Resource for Health Observers Series No. 17.

http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/WHO_GSHRH_DRAFT_05Jan16.pdf?ua=1.

World Health Organisation. (2019).WHO Guideline: Recommendations on digital

interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva, Switzerland.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311941/9789241550505-eng.pdf

World Health Organization. (2021). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025;

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland.

https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2022). Ethiopia emergency-preparedness.

Wynn, D. C., & Maier, A. M. (2022). Feedback systems in the design and development

process. Research in Engineering Design, 33(3), 273-306.